Below, Tom Bellamy shares five key insights from his new book, Smitten: Romantic Obsession, the Neuroscience of Limerence, and How to Make Love Last.

Tom is a neuroscientist and Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham. He has published over 40 scientific papers, abstracts, and book chapters on esoteric aspects of neurophysiology. His blog, “Living with Limerence,” offers practical guidance on coping with unwanted infatuation.

What’s the big idea?

Limerence—the obsessive, all-consuming early stage of love—feels like being struck by something supernatural. Euphoria, anxiety, daydreams, and intrusive thoughts all narrow toward a single goal: union with the beloved. But it’s not magic. The neuroscience behind intense infatuation can finally explain why love often feels uncontrollable.

1. Limerence is surprisingly common.

If you describe the symptoms of limerence to people, you tend to get two kinds of responses. Either: “that’s just love, you don’t need a special word for that”, or “that sounds obsessive and unhealthy.”

Here are eight key symptoms of limerence:

- Perceived signs of reciprocation from the “limerent object” (the person you’re infatuated with) cause an intoxicating natural high—a feeling of buoyancy, energy and euphoria.

- Perceived signs of disinterest from them cause intense anxiety.

- Frequent daydreaming and rumination about them—often used for mood repair, because it gives some fleeting relief.

- They seem to have a special, almost uncanny, romantic potency for you.

- Mental preoccupation and intrusive thoughts so bad that it makes it hard to concentrate on other tasks.

- An aching sensation in the heart when uncertainty is high.

- A powerful desire to form an intimate pair bond with them.

- Wanting above all else for them to feel the same way about you.

Now, there is more to the experience of limerence, but those key symptoms should let you know whether you have experienced it. When I surveyed 1,500 adults in the U.S. and the UK about whether they’d ever experienced limerence, just over half said yes.

That means that half the world expects love to feel like those flights of exquisite agony described by the poets. The other half expects it to be a wonderful boost to life, certainly, but not such a wild extravagance of emotions that totally transform you. Those conflicting instincts are responsible for a lot of heartache.

Each “love tribe” looks for their own feelings to be reflected to them, not realising that half the world is feeling something very different. A lot of dating disasters can be explained by the mismatched expectations of the two tribes when they encounter each other in the wild.

2. People can be addictive.

Dorothy Tennov first defined limerence in the 1970s, but we’ve had half a century of neuroscience and psychology research since then. Modern neuroscience can make sense of the symptoms of limerence in terms of the fundamental mechanisms of the brain.

Co-activation of three neural systems—the arousal, reward, and bonding systems—can imprint a particular person as an extraordinary natural reward. They become, effectively, a supernormal stimulus.

Under the right—or maybe, wrong—conditions, the drive to seek that romantic reward can become so powerfully reinforced that it becomes an addiction. They say love is a drug, but we really can become addicted to another person.

“They become, effectively, a supernormal stimulus.”

One of the biggest drivers for the development of this addictive state is uncertainty. Because of the way that the dopamine reward system operates, if we can’t be sure about how our limerent object feels about us, it intensifies desire and weakens self-control. If a reward is unpredictable, we want it more. Hope plus uncertainty is the killer combination for driving limerence into a state of person addiction.

3. Why we can’t give them up.

If a limerent can form a relationship with their limerent object, then the wildest emotions will naturally subside. However, if indecision, barriers, or unpredictable behavior from either person frustrate the limerent drive, then the transition to person addiction can set in.

Unfortunately, that means that people who mess with your emotions and give you mixed messages can be especially addictive. This perverse outcome stems from another peculiarity of the brain: wanting and liking are separate processes with distinct neurotransmitter systems, and they can become uncoupled.

If the motivational drive of dopamine is reinforced for long enough, it can make you want things—or people—that you no longer even like; that no longer give you the pleasurable hedonic hit of endorphins. This is why we sometimes can’t stop craving people who make us feel bad, or who treat us badly, or who we know there’s just no future with.

The irrational behaviour of limerents who are endlessly hung up on a hopeless case—much to the despair of their friends—lies in the fact that we can accidentally train ourselves into an abnormally powerful state of wanting that feels impossible to resist. That confusing blend of pain and desire can persist for years, trapping the limerent in a state of mental limbo that overshadows any new romantic opportunities.

4. The online world reinforces limerence.

The combination of hope and uncertainty is the surest way to drive the giddy intoxication of limerence into the queasy desperation of person addiction. Unfortunately, many of the ways that people seek love in the modern world seem tailored to promote it.

“The online world promotes the rumination and idealization that feeds limerence.”

From picking strangers on dating apps based on a few carefully curated pictures and some sales patter, to the endless database of personal information on social media that a limerent can immerse themselves in. The online world promotes the rumination and idealization that feeds limerence. As one of the readers of my blog put it:

It’s astonishing the power of social media on a limerent. Something as innocuous as a new profile picture and I am ruined. I know I should hide her from my feed, but that’s about as effective as locking the liquor cabinet when the alcoholic still has the key.

It is easier than ever to lose yourself in wishful thinking and drive yourself crazy with the power of intermittent reward, as you browse social media and wait for likes, comments, or DMs from your limerent object. As another reader put it:

I used to go on Facebook obsessively to see if he had liked my last post. I’d get such a rush of excitement when he did. It ended up getting to the stage where almost everything I posted was chosen to try and get a like out of him.

5. How to recover from unwanted limerence.

Out of curiosity, I once asked the community at livingwithlimerence.com “would you turn off your limerence if you could?” The answers illustrate the central emotional conflict:

- I know I SHOULD turn it off, but I’m not sure I would. It makes me feel alive.”

- Limerence has been a bittersweet experience, that’s how I can sum it up. The highs are awesome, one is literally on cloud nine. The lows, on the other hand, suck big time.”

Limerence is addictive because it feels wonderful at first, but it’s not hard to think of times when you need to free yourself from what’s become a debilitating obsession. Fortunately, recognizing that limerence can become a behavioral addiction offers a way out. You need to reverse the brain training habits that reinforced the addiction.

There are three key steps:

- Limit contact. Cut off the source of supply by breaking both direct and indirect contact with your limerent object.

- Train your executive brain. Following your instincts leads deeper into limerence. You need to exercise your prefrontal cortex to overrule those urges and interrupt the habit cycle.

- Spoil rewards. Fundamentally, you’ve subconsciously linked the promise of romantic bliss to another person. You need to break that association and break the idealization before recovery is possible.

It’s not easy to develop the habits of mind needed to reverse person addiction, but it can be done.

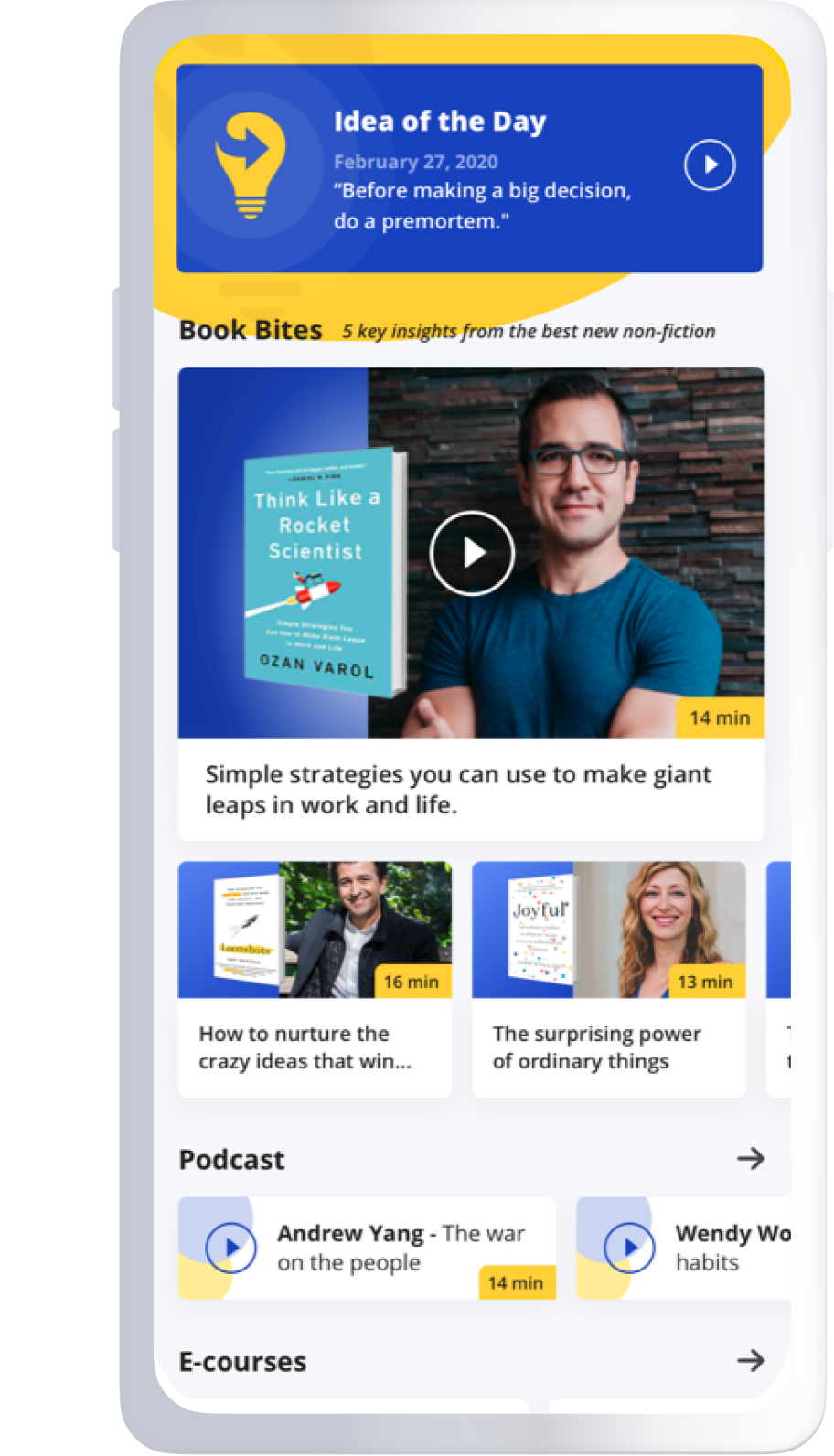

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: